Briony Downes is an arts writer and this feature story is published in partnership with Art Guide Australia.

Edna Walling’s living legacy

An exhibition in Melbourne’s east presents the work of artists and landscape architects whose creative practice draws on the life and work of renowned Australian landscape designer, Edna Walling.

In gardening and landscape design circles, Edna Walling is considered royalty. Migrating to Australia from the UK in 1899 when she was fourteen, Walling studied at Victoria’s Burnley Horticultural College and went on to become one of Australia’s most influential landscape designers. Not only did she pioneer the use of native plants and initiate her own urban development while still in her mid 20s, throughout her life Walling also wrote prolifically on gardening for magazines and books. Her designs, both formal and informal, can be seen in gardens throughout southern Australia, many of which were early examples of sustainable gardens, favouring drought hardy native plants over introduced species.

Achieving this as a woman working independently in 1920s and 1930s Australia would have been no small feat. Indeed, Walling projects an image of a determined and industrious woman and is considered by some to be an early feminist and conservationist. Initially influenced by English horticulturist and gardener Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932), Walling began her career working in the Arts and Crafts style of gardening, where bespoke design was key. This paved the way for a more informal style of planting, which replaced traditionally Eurocentric straight borders with the softer edges of non-defined boundaries and a keen interest in natural elements indigenous to Australia.

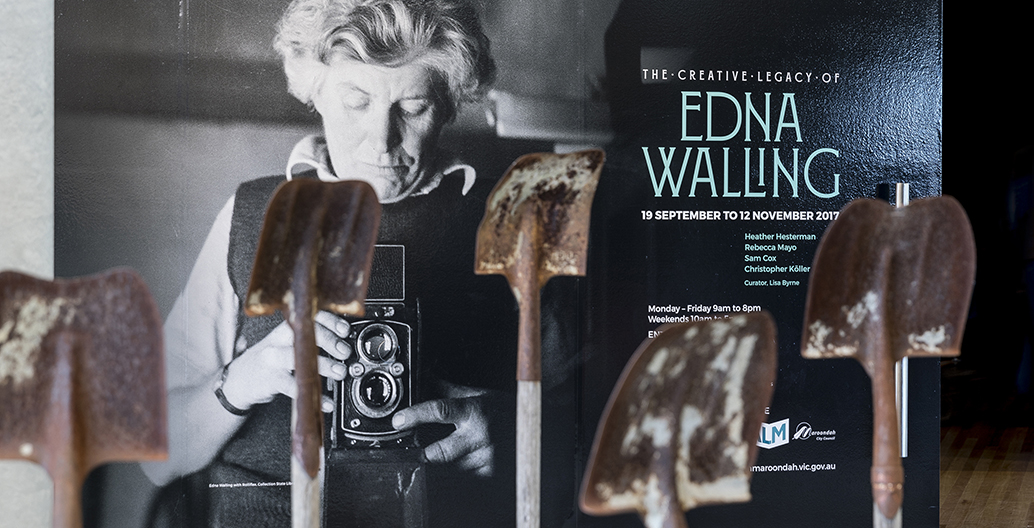

Along with friends and colleagues, such as botanist and wildflower expert Jean Galbraith (1906-1999), Walling began to use native plants in her designs to create a strong sense of place and belonging. The ripples of this legacy can still be felt in contemporary landscape design and this phenomenon forms the central theme of an exhibition being held at Maroondah’s ArtSpace at Realm (located in Melbourne’s outer eastern region). Curated by Lisa Byrne, The Creative Legacy of Edna Walling explores the impact Walling has had on Australian artists and landscape designers.

The Creative Legacy of Edna Walling explores the impact Walling has had on Australian artists and landscape designers.

Potato Throw by Rebecca Mayo.

The Diggers by Sam Cox.

The Creative Legacy of Edna Walling, ArtSpace at Realm, Melbourne, September 19 to 12 November

Byrne was first introduced to Walling’s gardens several years ago while researching the bluestone homesteads of Melbourne’s Western District. “It was evident Edna had many strong ideas and beliefs that have to this day remained pertinent in landscape design,” Byrne says. “Most importantly, she had ideas about our use of land and how it is carved up for built structures.” Given Walling’s keen interest in conservation (she was known to go on surreptitious nighttime missions around Melbourne, pulling out introduced species and replacing them with local natives), Byrne found that numerous gardens designed by Walling in Victoria possessed a distinctive, naturalistic style.

Walling’s endeavours also extended to photography, writing and painting. To illustrate her ideas within a contemporary art gallery context, for the past twelve months Byrne has been working with four creative practitioners who were asked to respond to the breadth of Walling’s legacy. “Edna was an early feminist, working in a labor field when most women did not have careers,” Byrne explains. “As a curator interested in social history and how to explore these ideas through art and design, Walling’s spirit captured my imagination.” She invited Rebecca Mayo, Christopher Koller, Heather Hesterman and Sam Cox to explore this legacy through installation, video, textiles, and ceramics.

Sam Cox, a landscape designer based in Eltham, Victoria, has a strong background in naturalist landscaping. Not only is he the grandson of notable Professor of Botany, John S. Turner (1908-1991), Cox was also mentored and employed by landscape designer and rockwork master, Gordon Ford (1918-1999). Ford was in turn influenced by Walling and Ellis Stones (1895-1975), to the extent that he was nearly poached by Walling to join her in landscaping endeavours. “The famous story is that Edna actually wrote Gordon a letter, asking him to come and work for her,” Cox reveals. “Gordon had begun to work with the removal of straight lines and undefined borders so he was pioneering new directions in garden design too. When Gordon spoke of Edna, it was always as landscape royalty. She was the first colonialist to pioneer a sense of belonging in a country through the use of native plants.”

For Byrne’s exhibition, Cox has created a shovel cemetery inside the gallery where several shovels stand like gravestones, wedged into concrete pots covered in a mound of mulch. A recreation of a similar feature in his own garden, Cox says the idea came from a broken wheelbarrow cemetery Ford constructed as a final resting place for old garden tools. “Creating a piece for a gallery was initially daunting but I found that there were similar aspects to designing landscape,” he says. “With landscape design, you are always picturing and imagining how to create a space. The Diggers recreates the hands-on approach Walling had and visually demonstrates how outdoor labour has influenced my own practice. The legacy of Edna Walling, for me, is her hands-on approach to construction and development.”

Cox describes Walling’s practice further, “The classic Walling elements of landscape design are naturalism, non-defined boundaries and planting out the fence line. Elements of mass and void. Privacy for buildings was also key. Through her garden design Walling would create a kind of envelope for buildings to sit in, which is still quite a Eurocentric approach. She loved roadside verges and natives but this came later in life.”

One of Walling’s most enduring and well known projects is Bickleigh Vale Village in Mooralbark. Possessing a love for construction, Walling became arguably Australia’s first female property developer when she bought acreage there in 1921. Here, Walling designed houses and gardens in the style of the English Cottage Garden and while the urban landscape has since replaced the open paddocks Walling was accustomed to, many of Bickleigh Vale’s original features remain. Glimpses of wooden shingles, low level stone walls and meandering paths occasionally peek through the foliage of Walling’s beloved birch trees, native shrubs, ground covers and hardy perennials.

“For her to purchase and develop her own land at that time would have taken a very powerful mind to accomplish,” says Cox. “Bickleigh Vale is an extension of that powerful mind. In many ways, Edna and her friends were literally building a community in itself.”

During her lifetime, Walling owned a number of properties. In the 1950s she purchased a steep pocket of land on the Victorian coast near the Great Ocean Road. With help from her friends Rosamond Dowling and Joan Niewand, she built a holiday chalet in the bush and documented the experience in her book, The Happiest Days of My Life. In keeping with her environmental concerns, it was essential to Walling that the building impact on the surrounding environment as little as possible.

For the exhibition, Heather Hesterman, an artist and landscape designer with LushPlot, has created work responding to this property and the sense of community Walling fostered there. As an artist who works across contemporary art and landscape design, Hesterman was inspired by the small clay pots Walling witnessed a friend make, by hand, to protect diminutive plants destined for the chalet. To create BUILT: For Rosa and Twid with love, Hesterman engaged the public in a series of pottery workshops, the outcome of which are the hundreds of tiny pots on display in the gallery.

Built for Rosa and Twid with Love by Heather Hesterman.

Winter Walling, Octagonal Pool by Christopher Koller.

‘Our first dining room with the A.W.A.S. against a rock’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, SLV.

Describing the communal process behind making the pots, Hesterman says, “Clay was bagged up with instructions and these ‘clay packs’ were distributed far and wide. I invited Spensley Street Primary School and the Wyreena Community Arts Centre to participate in several pot making workshops. Although some adults had heard of Edna Walling, many didn’t realise that she was one of the earliest environmentalists to advocate the planting of Australian native species.”

Walling’s love for native species was a catalyst in her growing concern for the impact highways were having on the natural environment. To make way for burgeoning car culture, roads were being widened and straightened, subsequently destroying the roadside verges around them. Artist Rebecca Mayo’s installation Potato Throw references Walling’s haphazard method of spreading seeds from a bucket and the regular journeys she made between Melbourne and Adelaide, where she often stopped overnight to pitch a swag in nearby bushland.

Driving a similar route between Melbourne and Adelaide, Mayo stopped at various intervals to throw potatoes onto lengths of fabric, marking where they fell with hand sewn stitches before potato-printing over the patterns back in the studio. In the gallery, the lengths of fabric are pitched like billowing tents, a playful homage to Walling’s independence and adventurous use of space.

“Walling worked with the natural form and undulation of the landscape in her gardens, while still creating her garden rooms,” says Mayo. ”My fabric tent forms can be seen as spaces within spaces. When you look through the work, intimate views of folding fabric are experienced.” When driving, Mayo often thought of Walling, especially during the many roadside walks that broke up the trip. “It was the moments when we stopped to throw the potatoes that I thought most about Walling. Perhaps she also stopped nearby, for lunch with her mum or a friend. Some people think it is a very boring drive, quite flat and straight. But for me it is a thread connecting my two homes.”

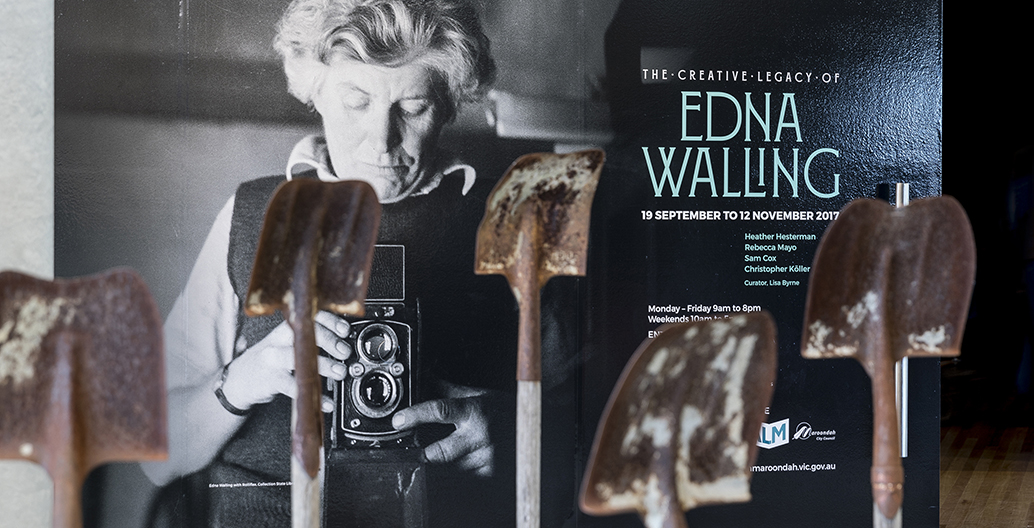

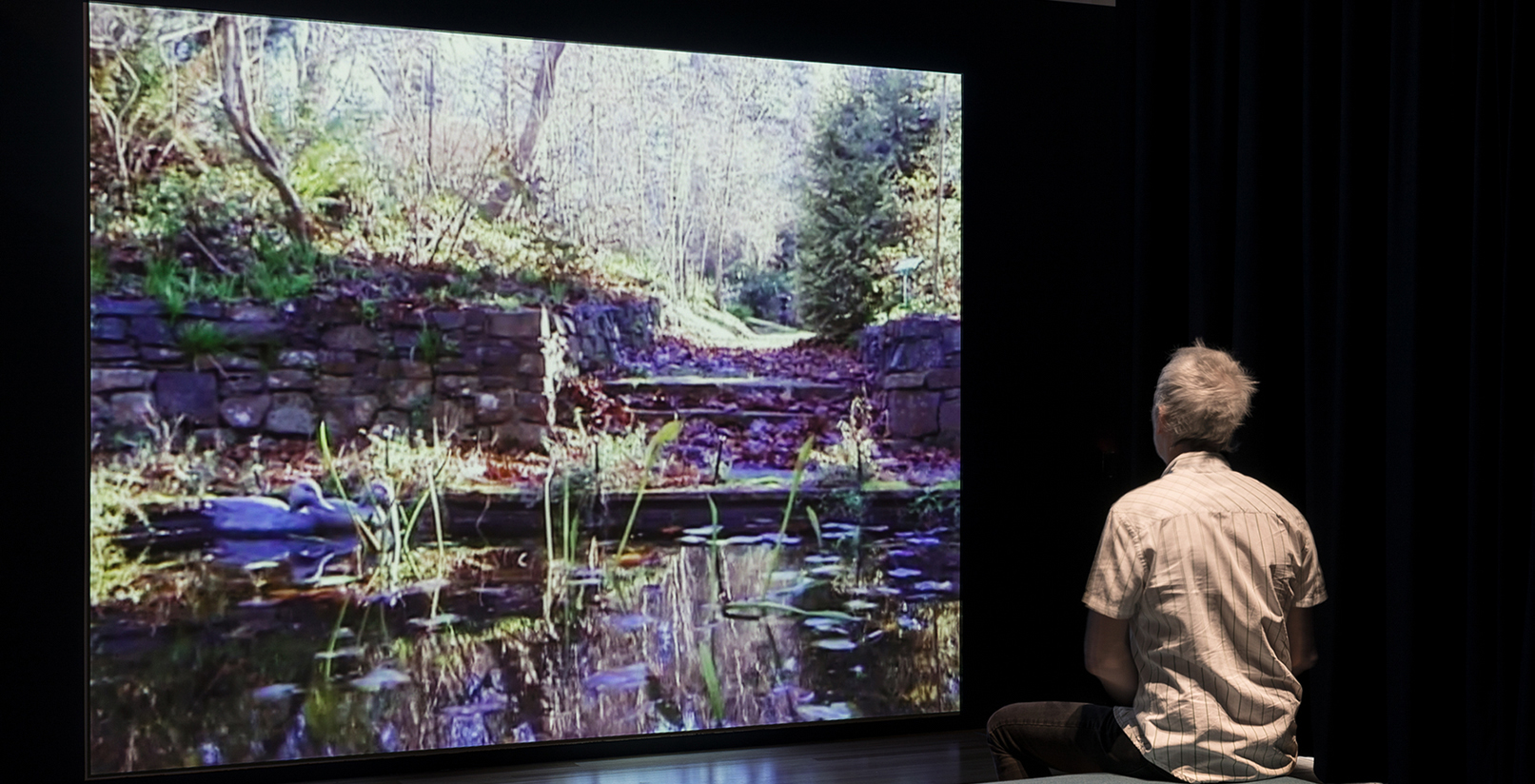

Arguably, Walling’s most famous garden design is The Grove at Mawarra Manor in Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges. Stonework is predominant, with moss coated pathways leading through low hanging foliage to discreet locations. It was here artist Christopher Koller used photography and film to document the changes winter brought to the garden in his work Winter Walling, Octagonal Pool, 2006. Capturing the garden from the centre of Walling’s striking pool, Koller offers a unique perspective of her sweeping stone staircase and scattered plantings of European Beech Trees.

With renewed interest in Walling’s work leading to the recent restoration of The Grove garden at Mawarra Manor and a new generation of gardeners and artists continuing to be inspired by her work, Walling’s legacy endures. Citing the exhibition and the scope of Walling’s practice, Cox concludes, “An exhibition like this is an important opportunity to revisit Walling’s work and rediscover how much influence she has had on the landscape of Melbourne and beyond. There are so many places that she helped to develop and it is really important to keep that knowledge alive.”

––

The Creative Legacy of Edna Walling was showing in Melbourne at ArtSpace at Realm, 179 Maroondah Highway, Ringwood from 19 September to 12 November 2017. Sam Cox will be a speaker at the Australian Landscape Conference 2018.